中东有石油,中国有稀土。

“The Middle East has its oil, China has rare earth”

Deng Xiaoping, 1992

She must have got back to work by now. But holidays had never felt so good. A much-needed break from the hectic pace of her office job.

The station was thronged with passengers, their incessant chatter turning into a constant background hum pierced only by shrill whistles. Luckily, her Beats headset cancelled out the noise, muffling the hubbub, and so she could just let herself be carried away by the music. All of a sudden, a vibrating alert made her reach for her pocket. A reminder had flashed up. With a swift movement, she swiped the message away. Then, she swivelled her slim wheelie suitcase, tapping on the screen with the other hand as she made for the platform. She easily overtook a middle-aged man who was trundling an overloaded trolley, puffing and panting as he slowly ploughed his way to his train. You’d better travel light unless you want to pick up a nasty injury and spend the rest of the Festival in bed, with granny greasing you like a duck with her magic ointments for back pain. She giggled. Presents for friends and family? Online shopping and home delivery, why would one bother going to stores anymore?

The sleek high-speed train was ready for the long journey inland, heading away from the sprawling megalopolis on the seaside. Her coach was the first, just behind the engine and no other fellow passenger had got there yet. Standing alone at the far end of the platform, she savoured this moment of calm. She hesitated before getting on board. Would auntie ask again the same questions, like, boyfriends and getting married? Sighing, the girl brushed aside these thoughts, and rapidly unlocked her Huawei. The shutter clicked. The selfie was lovely: the train windows were reflected in her oversized, stylish glasses, while, in the background, the passengers disappeared into a faint blur, indistinct shapes out of focus. “Smart travelling – standing out from the crowd”. She posted it online with one last tap, then a step on the footbridge, her back turned to Shanghai, looking ahead to the end of the tracks.

What’s in a quote

The account is fictional, the character is not. Kind of. A job as a sales manager, an undergraduate degree in business at a university abroad: you can learn so much about someone on LinkedIn, at least just enough to start inventing a believable character. We had exchanged a couple of e-mails before I received that message. It included two attachments: a formal quotation, and a brochure showing off a jaw-dropping list of customers worldwide. Would we become one of them?

Our laboratory needed a piece of equipment and I had been asked to shop around to get the best deal. This allowed me to embark on a tour of the five continents and the seven seas, well, at least a virtual one. After all, how does that old saying go? “Do science, see the world”, right? After going on a massive e-mailing spree worldwide (including a reckless sortie into Alibaba territory), I duly got spammed in return by sales representatives eager to satisfy my requirements and entice a new customer. When I finally tidied up the stack of e-mails in my inbox before reporting to my boss, I realised that two thirds of the quotations had come from Chinese companies, all of them based in the greater Shanghai area. In a sense, this came as a no surprise: I already knew that, in the context of the squeeze on research budgets, academics are increasingly turning to more affordable pieces of equipment. After all, ‘Made in China’ no longer means a cheap and low-quality, ‘better-than-nothing’ alternative; nowadays, it is rather a proxy for no-frills, reliable instruments that (usually) turn out to be sturdy workhorses and deliver the goods just as well as those manufactured by more renowned companies, while remaining by far more affordable.

Battery research has felt the full force of the rise of China as a global R&D superpower. Don’t worry – I will neither deliver a lecture on the latest plenary session of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, nor take sides in trade wars nor harp on about the skyrocketing number of scientific publications authored by my colleagues from the People’s Republic of China (PRC henceforth). Let me just remind you that the PRC has been implementing a plan called Made in China 2025, demystified in a superb BBC video explainer, which aims to make China a global leader in cutting-edge, research-intensive manufacturing. The overarching goal of this plan (purportedly inspired by Germany’s comparable Industrie 4.0) is a major overhaul of the PRC’s industrial sector to upgrade it with a special emphasis on domestic supply chains. What does it mean in practical terms? By 2025, high-tech goods will ideally include 70% of components made in China. Among the ten strategic sectors we can find “smart green cars”, “renewables” and “high-tech materials”: you could argue that batteries have a finger in every plug (ho ho!). It just takes a few minutes’ surfing on the Internet to see the incoming tide flowing from this sea-change: most of the world’s lithium-ion battery “megafactories” are (being built) in the PRC, which is following a coherent strategy to make the most of its own raw materials, as described by the journalist Guillaume Pitron in his article in Le Monde Diplomatique (English version):

China’s electric vehicle strategy is the world’s most ambitious. In 2015 the Made in China 2025 plan identified electric car batteries as an industrial priority. China’s huge domestic market allows economies of scale, which give its carmakers a competitive edge, and its production of rare metals has helped the initiative. The West, in offshoring its mining pollution, has handed its rival a near monopoly on raw materials strategic to the industry: China now produces 94% of the magnesium, 69% of the natural graphite and 84% of the tungsten consumed worldwide; for some rare earths, it’s as much as 95%.

(Yes, a whopping 95%. Now you can understand why Deng Xiaoping’s statement looks so visionary. If you are a battery-savvy reader, take note of the figure for graphite).

Coin collectors

Still not convinced? Follow me, let’s take a stroll in the battery lab and pretend to be a materials scientist. Say you have come up with an innovative/novel/ground-breaking battery material with unparalleled/unprecedented performance (the superlative is flourishing in the literature, as rightly criticised in this ACS Catalysis editorial) and you want to test it. One of the first things to do is quite simple, almost too trivial to be true, and not very different from making a sandwich. Pack your wonder powder into a small disc, stick it into a glovebox, pile up the first disc, a wet separator, and a lithium disc (Volta would simply love having a go!), crimp everything into a coin cell – yes, the very same little thing that powers wristwatches. Mind the polarity, and just keep charging and discharging the battery. At the same time, record the potential. That’s it? That’s it, except that you’d better repeat all the sequence for at least a handful of batteries (science is all about reproducibility, right?).

If you feel like trying yourself… (watch out: get some sturdy chemical-resistant butyl gloves, like the black ones you’ll see in the first video):

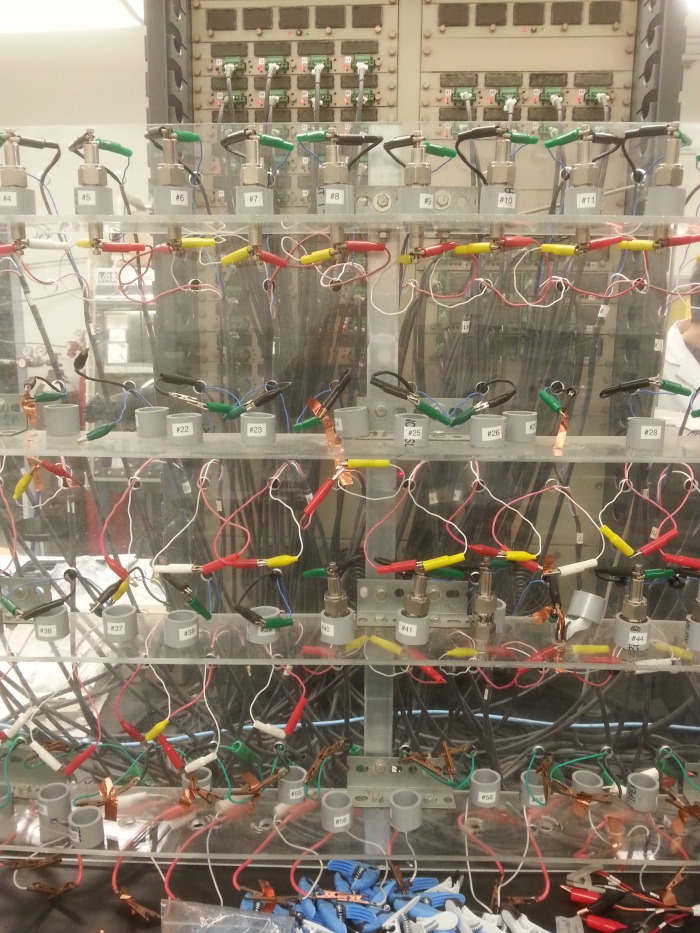

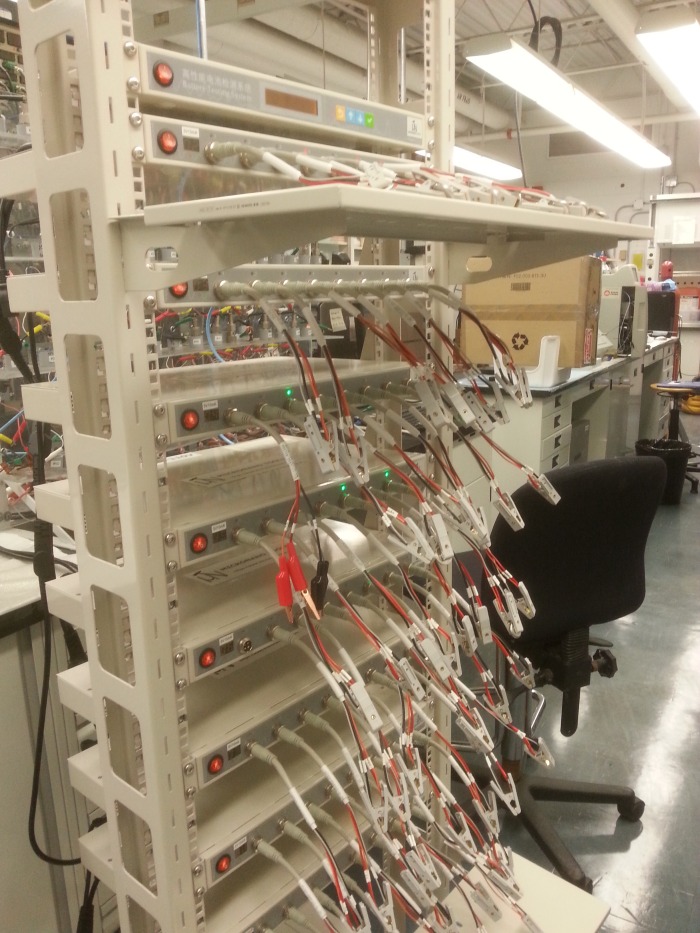

The piece of equipment that you need to run such a battery of tests is called – quite disappointingly – a battery tester. If you look at the two testers in our laboratory, you can see at a glance the two superpowers facing each other, China vs the US. The older tester, made in Texas, is a heavyweight box that looks like a vintage computer with huge cooling fans at the back and a thick canopy of cables branching from the instrument to the battery racks. It was probably manufactured in the 1990s and it is computer-controlled with a program that runs on MS-DOS – oh yeah, that dinosaur software, and if you recognise this abbreviation, welcome to the oldies’ club. This instrument has let us down quite a few times, the tester cutting out halfway through experiments. In spite of that, it still usually does the job.

Opposite the giant stands the slimmer tester made in PRC, composed of modules stacked on shelves, equipped with small wheels that make the instrument relatively portable. It’s a cliché, but I don’t resist the temptation: a martial arts master’s nimble footwork and graceful movements pitted against a wrestler’s massive bulk and brute force – we all know who wins in the end.

Plug-in required

But the battery tester from China did not really create a buzz when it first arrived – well, it did, but for all the wrong reasons. No English-language manual was provided. How could we possibly coax the battery tester into functioning properly if we did not speak a single word of Mandarin? Well, you first sort out the tangle of cables in the box and you make sure that and all jacks are properly connected. Easy. What next? Someone would have to decipher the script: a brave PhD student stepped up and started plugging away at this problem. A lot of e-mails and days later, he triumphantly worked out how to run the software, making the most of an abridged English-language manual that the manufacturers had especially translated for him, with a little help from online resources. (Take-home message: never write Google Translate off as a cheat).

Follow the script

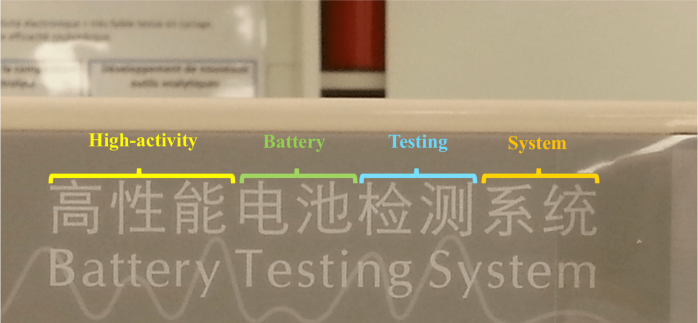

If there is one thing that immediately caught my attention when the battery tester was set up, it was the string of Chinese characters printed on the front panel of each module. I have always been fascinated by this script and rarely do I resist the temptation of trying to deconstruct the characters to work out their meaning. Moreover, it is exciting to think that unlocking the secret of the ideograms could also provide a shortcut to the mindset and worldview of those using this script. Intriguing, and dangerous at the same time: this sort of linguistic determinism may lead you down a slippery slope. Yes, neuroimaging (i.e. functional magnetic resonance) has shown that, when a subject is reading Chinese, very specific parts of the brain fire up (see for instance here and here). Nevertheless, we should not forget that “That which we call a rose/ By any other word would smell as sweet” (Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, a very suitable quote to mark Saint Valentine’s Day). José Saramago wisely wrote “words are labels put on things, they are not the things”2. It is reckless to make a fetish of words and to overload them with significance – unless you are writing poetry, but that’s another story.

Leaving dissertations on neurolinguistic aside, I find it hugely entertaining, to say the very least, to sit down and discover the origins and evolution of Chinese ideograms. If this is also a way of chipping a hole in the Great Language Wall denying access to Chinese culture, all the better. That’s why, to celebrate the Spring Festival in my own personal way, I borrowed a book entitled 100 mots pour comprendre les Chinois (by Cyrille J.-D. Javary, Albin Michel, 2008) – “Understanding the Chinese in 100 words”. What a tall order, and I have the gut feeling that the book does not fully lives up to the great expectations created by the title, but the challenge that it faced was formidable. On the other hand, it does appeal to a broad readership: those just looking for trivia will learn lots of anecdotes to impress colleagues at the next office bash, while the book will give an extra taste of Chinese culture to those already as keen as mustard. In short, I recommend this book as it makes for a very enjoyable read, well, provided that French is no double Dutch to you.

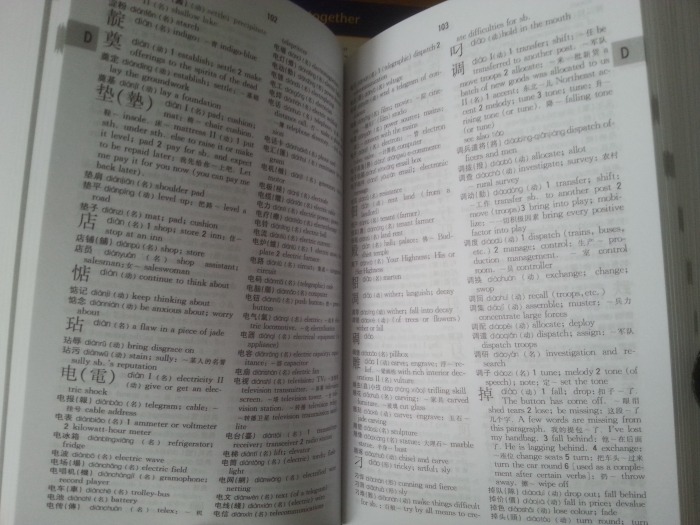

But we should not beat about the bush: the characters on the battery tester still need to be deciphered. At this point anyone familiar with the Chinese script will be laughing out loud saying: “Matteo behave, stop pretending you’re Indiana Jones trying to decipher Linear A, don’t kick up a fuss about nine characters. Just stick it into Google Translate and cut a long story short”. No, I want to crack the code the good old way, that is, I want to get to grips with the characters barehanded, as in martial arts, just with the help of a good old paper dictionary. Fully hand powered, and no need to worry about chargers: ink does not run on batteries, does it ?

A few minutes hours days later…

(which explains why I am late with my post, which I was supposed to publish on the first day of the Spring Festival, the 5th of February).

Grinning proudly, I had the translation checked by my colleague Mengyang, who gave me the thumbs-up. Look at ‘battery’, a beautifully simple combination of two characters: an electricity (电, diàn) reservoir (池, chí). I’d like to dwell a little longer on the first character, one of the hundred dealt with in the book I was talking about. It is written as 电 in simplified characters (i.e. the script in use in the PRC), while the traditional character (still in use in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macao) is 電 (choose your favourite). As Javary explains, we need to look at traditional characters if we wish to make out the composing parts and understand the ultimate meaning. If we break dian up, we recognise a top part, 雨 (yǔ), meaning ‘rain’, and a bottom half akin to 申, shēn. Javary points out that this is an old ideogram that conveys the idea of a vital force, a natural ‘spirit’. On the other hand, my faithful dictionary translates the character as ‘to state’, ‘to express’, and talking about Chinese Zodiac, this character also stands for ‘monkey’ (which will make its comeback only in 2028). So, it takes just a bit of imagination to see the character combining these two moieties, 雷 , as a clever shorthand for ‘something expressing rain’, and, lo and behold, it does mean ‘thunder’ (léi). But I’ve probably already gone too far in my linguistic antics. A lengthy dissertation on the origin Chinese characters falls beyond the scope of this post, and so we had better leave it at that.

Back to what matters, electricity. If you look carefully, our friend 電 is almost identical to thundery 雷. Find the difference. Yes, there’s an extra ‘hook’ added at the bottom, which, as Javary reminds us, is an ancient decorative motif having to do with ‘lightning’. ‘Electricity’ has thus an intimate connection with the sky’s most impressive phenomena, and, not surprisingly, 電 is indeed employed in a combination standing for ‘lightning’ (閃電 shǎndiàn)

Aptly enough, it also looks like that 電/电, in colloquial speech, conveys the ‘chemistry’ that you can have between people (both wiktionary). After all, ‘love at first sight’ becomes coup de foudre, ‘lightning strike’, in French.

(Quote unquote: an epilogue of sorts)

For a few days, I did not hear from her. We had sent her an e-mail asking for a revised quote including some optional parts. Then, all of a sudden I found a message from China: although it still looked very professional, I somehow had a hunch that it had been written in haste, amidst friends and family, while a flurry of firecrackers and fireworks was going off. Indeed, she apologised for her late reply and kindly reminded me that her would be on holiday until the 12th of February. I greatly appreciated the remark, and I decided not to bother her for the rest of her holidays. We still need more information before we can take a decision, and so I will probably drop her a line later today. By then, she will have gone through the massive stack of e-mails that she must have received during the holidays. When I sit down and start typing, it will be so hard to resist the strong temptation to let her know what happened. How the no-nonsense, business correspondence that we had exchanged by a lucky coincidence just before the Spring Festival took me on an exciting journey through Chinese characters and culture, as far as the very metropolis where she lives and works.

Because this is what that quote really meant. “Do science, see the world” is an invitation to keep our eyes open, to be curious, to make the most of science as a means to explore and appreciate the world in its entirety, while meeting lovely, interesting people on the way.

And, as we have learned, it’s only a short step from batteries to electricity and thrilling chemistry.

It’s electric when you click.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully thank Mengyang for her infinite patience. 谢谢 !

He’s the one who finally got it cracked. Quentin is a veritable unsung hero.

The beautiful photos from Lisbon are courtesy of Rita and her friend. Both are kindly acknowledged.

Footnotes

1 The full original quote, retrieved online, reads: 中东有石油,中国有稀土,中国的稀土资源占世界已知储量的80%,其地位可以和中东的石油相比,具有极其重要的战略意义,一定要把稀土的事情办好,把我国的稀土优势发挥出来。”The Middle East has its oil, China has rare earth: China’s rare earth deposits account for 80 percent of identified global reserves, you can compare the status of these reserves to that of oil in the Middle East: it is of extremely important strategic significance; we must be sure to handle the rare earth issue properly and make the fullest use of our country’s advantage in rare earth resources.”

2 From As Intermitências da Morte (“Death at Intervals”): “As palavras são rótulos que se pegam às cousas, não são as cousas, nunca saberá como são as cousas, nem sequer que nomes são na realidade os seus, porque os nomes que lhes deste não são mais que isso, os nomes que lhes deste“